Taken Up?

On the Veracity of the Rapture

In the previous article, we addressed the claims of dispensationalist theology regarding the promises to Abraham, the nation of Israel , and the people of God. Following this, I have prepared a further article dealing with, what I think at least, is the second most pervasive element of this modern Christian theological framework - namely, the rapture.

The concept of ‘the rapture’, the event in which the faithful church shall be taken away from the earth either before, during, or after the period of tribulation which is to precede the last days, is a central concept - indeed, a nigh doctrine - within many contemporary forms Christian eschatology. It is a necessary component for dispensationalist teachings, which also imply a literal covenant with the ethnic nation of Israel, and a literal millennial reign of Christ on earth at the end of the age. All of these together form the central interpretative praxis of their salvific and eschatological model, whereby the Church is removed in order for God to re-establish his covenant, (and this his saving work) with the ethnic Jews of modern Israel during the last days - ain order that he may bring his Church back to reign with them for a thousand years.

We have already shown that such an interpretation of the covenant with Abraham in Genesis 15 and those with ethnic Israel throughout the Scriptures, upon which all of this is predicated, is dubious. This is apparent when we understand the lens of St Paul’s theology in Romans and Galatians and indeed, the rest of the NT, along with the early consensus of the Fathers. As we have shown, such a insistence does serious damage to the salvific implications of the gospel, and gives rise to many further faulty interpretations. We will demonstrate this by now turning our attention to the associated concept of the rapture.

The Rapture - A Historical Perspective

Before we examine the biblical portrait I think I would be useful to briefly outline the history of this interpretation. Like dispensationalism as a whole, the concept of a ‘rapture’ is quite novel. It is often argued that the earliest mention one can find of any such concept is from Darby and Schofield’s Reference Bible (c. 1909) - the same work from which the entire dispensationalist framework was first articulated in the late 19th and early 20th century.

This is not, however, entirely true. Indeed, there are some instances wherein a supposed rapture, specifically a ‘pre-tribulation’ kind, is noted. The first is quite striking:

“Why therefore do we not reject every care of earthly actions and prepare ourselves for the meeting of the Lord Christ, so that he may draw us from the confusion, which overwhelms all the world? . . . For all the saints and elect of God are gathered, prior to the tribulation that is to come, and are taken to the Lord lest they see the confusion that is to overwhelm the world because of our sins.”

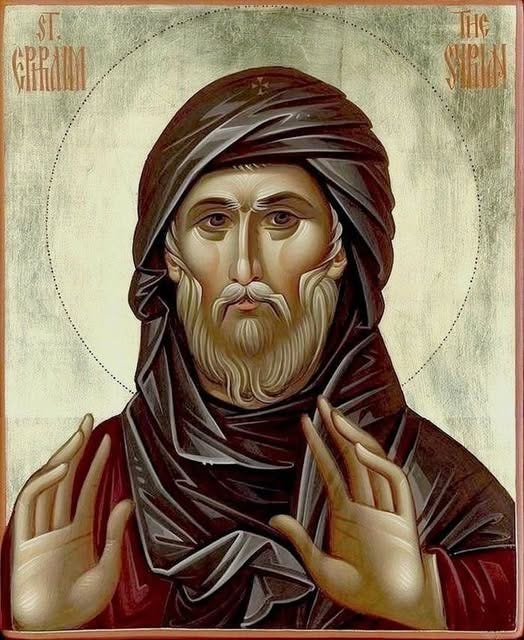

[Pseudo-Ephraim, Sermon on the Last Times, 2-3.]

This passage certainly seems to attest to a relatively early understanding among some Christians of a ‘rapture’ before the tribulation. Indeed, Rice may be correct in concluding that that “the sermon… represents a prophetic view of a pre-trib rapture within the orthodox circles of its day”.1 Nevertheless, we must also consider the fact that this text was most likely not written by St Ephraim the Syrian [AD. 306-373] but is instead dated by most scholars to much later - possibly to the sixth or seventh century.2 While this does not entirely erase it’s relevance as evidence for an early attestation of this doctrine, it also does not affirm it’s general acceptance among the broader orthodoxy (which certainly was not the case) - instead, ascribing it to the fringes of the general consensus.

Another example can be deduced from a 14th century account concerning a group of Franciscan monks known as the ‘Dolcinites’. Their leader, Dolcino, taught that he and his faithful followers would be taken to paradise “to be with Enoch and Elijah” during the tribulation of God’s wrath. Thereafter, he - having become the “true pope” (a claim unlikely to sit well with modern evangelical dispensationalists) - would return with his followers to instruct the survivors of the earth in the true faith. This is not so much evidence for the dispensationalist concept of the rapture as it is an example of the fanatic ravings of a religious sect later anathematized by the Roman Church.3 Far from providing early attestations of the rapture then, such accounts represent isolated and fringe beliefs that cannot be taken to reflect the orthodox faith of the broader Christian tradition.4

While it is also true that the word itself - from the Latin raptus “taken up” - appears in the early Latin text of Scripture and in subsequent Latin Fathers, it certainly does not carry the implied meaning of modern dispensational theology. Quite the opposite - this word is almost always used in reference to a ‘spiritual ecstasy’ or else another way of speaking about death [cf. Tertullian De Anima 55; St Cyprian of Carthage De Mortalitate 26.] Nowhere does it refer to a literal ‘taking up’ of the Church.

From a purely historical perspective, the concept of ‘the rapture’ is simply not representative of the vast majority of early Christian theological or eschatological frameworks - even those that affirm a literal millennium.5 And while this is not necessarily a problem for the dispensationalist - particularly those that would affirm a more literal sense of progressive revelation (though I would say that is a little dubious in this regards) - the fact that this supposedly central doctrine of Christian eschatology was almost completely absent from the first 1800 years of the Church is cause for concern. What does this mean for the work of the Holy Spirit? Indeed, the one who was supposed to have “lead [the Church] in all truth” [Jn 16.13] as a seal and sign of Christ’s headship and presence - “behold I am with you until the end of the age” [Matt 28.20]. What then are we to say of the faith that was “once and for all delivered to the saints” [Jude 3], that which has been believed “everywhere, always, and by all,” [St Vincent of Lorens, Commonitorium, 2]? Indeed, when faced with these questions, the dispensationalist is forced to conclude that the early church either was simply ignorant, or else that the Holy Spirit saw it fit to not share this vital doctrine with them - both conclusions would should be very hesitant to make.

One Shall be Taken, and the Other Left

Turning from the historical context of our discussion, we can bring our attention to the group of ‘prooftexts’ that are usually associated with this doctrine and evaluate their veracity.

We have already shown that ‘proof texting’ - the means by which one ‘backs up’ any given theological position by picking various texts (usually out of context) is a fraught exercise. This is nowhere more true than in the many such texts that are selected in order to ‘prove’ the concept of the rapture. The first supposed ‘rapture’ text often used in defending this concept is that of the Olivet discourse in Matt 24.36-44. The pericope mentions some who are ‘taken’ and others who are ‘left behind’, and is thus construed as a clear example of rapture theology:

“…then shall two be in the field; the one shall be taken [παραλαμβάνω], and the other left. Two shall be grinding at the mill; the one shall be taken [παραλαμβάνω], and the other left. Watch therefore: for ye know not what hour your Lord doth come…”

[Matt 24.40-42]

Yet a common misconception is the context of this particular part of Christ’s discourse, a crucial detail that is almost always overlooked by those who use the text in this way. Let us read the immediate preceding verses:

“But as the days of Noah were, so shall also the coming of the Son of man be. For as in the days that were before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day that Noah entered into the ark, And knew not until the flood came, and took [αἴρω] them all away; so shall also the coming of the Son of man shall be.”

[Matt 24.37-39]

Note the meaning of ‘taken’ [αἴρω] in Christ’s earlier exposition on the story of Noah. Though a different verb is used, both imply a similar meaning “taken away, removed”. Christ clarifies this in his subsequent, and stronger emphasise, with [παραλαμβάνω] ‘taken away’ in his application.

Who, then, is ‘taken’? Who is ‘left’? Is it not the wicked who are ‘taken’ in the judgment of the flood? This is certainly what the flow of the passage would suggest. This would imply that those who are ‘left behind’ are Noah and his family, those who are spared and saved within the ark. It is thus the wicked who are ‘taken’ away, in judgment - quite the opposite from how this text is often employed. Indeed, why would Christ swap the meaning of ‘αἴρω’ half way through his application? We must conclude, rather, that Christ intends those who are ‘taken’ to be understood as those who are removed in the judgment at the coming of the Lord, leaving those who are left as the saints and the faithful, those who will rule with Christ on the earth in the new creation [cf. Apoc 5.10].

We Shall be Caught Up in the Air

A similar error is shown in the interpretation of another appropriated proof text for the ‘rapture’:

“…for the Lord himself shall descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God: and the dead in Christ shall rise first: Then we which are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air: and so shall we ever be with the Lord.”

[1 Thess 4:16–17.]

Again, let us first turn to the context of this text:

“But we do not want you to be uninformed, brothers, about those who are asleep, that you may not grieve as others do who have no hope. For since we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so, through Jesus, God will bring with him those who have fallen asleep. For this we declare to you by a word from the Lord, that we who are alive, who are left until the coming of the Lord, will not precede those who have fallen asleep.”

[1 Thess 4.13-15.]

St Paul’s immediate concern in this passage is the pastoral care of the church of Thessaloniki, who, having heard various teachings on the Parousia and the resurrection of the dead, are concerned that their loved ones would miss out on the coming of the Lord. This is a persecuted church, many of the individuals who had fallen asleep may likely have been martyrs. The immediate concern for the church, then, is not a glimpse into the mysteries of the end times, and the establishment of a framework by which they may predict the coming end, but a deeply personal and pastoral one. What is the hope for my brothers and sister who have ‘run the race’ and ‘fallen asleep’?

St Paul’s response must be read in this context. A context which proof texting damages. I repeat. This is a response of pastoral care, not of end times prophecy. Thus, when St Paul says, “this we declare to you by a word from the Lord” this should be understood as a teaching of Christ while he was on earth, one of the ἄγραφα ‘unwritten’ teachings, [Jn 21.25; cf. Acts 20.35; 1 Cor 7.10, 9.14]. This may have been a response given to his disciples, most likely within the context of the Olivet Discourse, which we have just discussed.

What is the hope that St Paul gives to the church of Thessaloniki? That the church, at the coming of the Lord, shall be caught up with ‘them’. Who is ‘them’? The saints, the very ones “who have fallen sleep” which the church is concerned about. They shall not miss out on the coming of the Lord. Rather, they shall have ‘front row seats’, as it were, and shall “rise first.” It is thus both the faithful departed, the saints who have gone before us in glory, and those of us who are alive at the Parousia, that go up to meet the Lord and share in the victorious coming of the King.

At the Last Day

Yet this this cannot be understood as a partial coming of the saviour, a ‘pretribulation, pre-parousia, pre-general resurrection’ taking away, or ‘rapture’ of the Church... as it is often understood to show. Why? Because Christ is clear that the raising of the dead will occur ‘at the end’:

And this is the will of him that sent me, that every one which sees the Son, and believes in him, may have everlasting life: and I will raise him up at the last day.”

[Jn 6.40, 54].

The raising of the righteous coincides with the raising of the wicked:

“Immediately after the tribulation of those days the sun will be darkened…

Then will appear the sign of the Son of Man in heaven, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn,

and they will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory.

And he will send out his angels with a loud trumpet call, and they will gather his elect from the four winds, from one end of heaven to the other.[Matt 24.29–31]

“The harvest is the end of the age, and the reapers are angels. Just as the weeds are gathered and burned with fire, so will it be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will gather out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all law-breakers, and throw them into the fiery furnace. In that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. He who has ears, let him hear.

[Matt 13.39-41.]

Christ clearly echoes the words of the prophet Daniel here:

“The hour is coming when all who are in the tombs will hear his voice and come out — those who have done good to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil to the resurrection of judgment.”

[Jn 5.28-29]

“At that time shall arise Michael, the great prince who has charge of your people.

And there shall be a time of trouble, such as never has been since there was a nation till that time.

But at that time your people shall be delivered, everyone whose name shall be found written in the book.

And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake,

some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.

And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the firmament,

and those who turn many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.”[Dan 12.1-3]

St Paul seems to echo this in his extensive discussion regarding the resurrection in his first epistle to the Corinthians:

But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have died. For since death came through a human being, the resurrection of the dead has also come through a human being; for as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ. But each in his own order: Christ the first fruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ. Then comes the end, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father, after he has destroyed every ruler and every authority and power

[1 Cor 15.20–24]

“Listen, I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed.”

[1 Co 15.51–52]

It is abundantly clear form these passages that the resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked occurs at the end. What’s more, from St Paul’s comments in 1 Corinthians, we can see that this coincides with the glorification of the saints on earth, or as he says in 1 Thessalonians, “those who are alive shall be taken up with them”, that is, they will be glorified, changed, exalted with with those who are raised on the last day, to meet the Lord at his coming, along with angels and archangels, and all the host of heaven. But the immediate context of all these verses shows that this cannot be read as a ‘pre-tribulation’ event, nor one that precedes the climactic coming of the Lord. For in the Olivet discourse, the Parousia, the coming of the Son of Man, is the climatic conclusion, after the tribulation of the present age (Matt 24.29–31) after which follows the immediate enthronement of the Lord, the glorification of the saints, and the judgment of the world (1 Cor 15. 24-25; Matt 25.31–46).

St Augustine makes this much clear when he writes:

“These words of the apostle most distinctly proclaim the future resurrection of the dead, when the Lord Christ shall come to judge the quick and the dead.”

[St Augustine, City of God, 20.20]

Understood within this context, St Paul’s words cannot, therefore, be taken as a reference to the ‘rapture’ of the Church from earth before the tribulation, but rather, must be read in context - as the consummation of history. In these passages, the apostles proclaim the coming together of the Church, militant and triumphant to meet the final and glorious entrance of the King who has returned to restore the earth and judged the living and the dead.

To Meet the Lord at His Coming

St John Chrysostom understood the ‘meeting’ [ἀπάντησις] in the air, in exactly this way - as the coming together of the Church, both the faithful departed and the living, and their going out to meet [ἀπάντησις] the Lord in his glory:

“If he is about to descend, on what account shall we be caught up? For the sake of honor. For when a king drives into a city, those who are in honor go out to meet him; but the condemned await the judge within. And upon the coming of an affectionate father, his children indeed, and those who are worthy to be his children, are taken out in a chariot, that they may see and kiss him; but the housekeepers who have offended him remain within. We are carried upon the chariot of our Father. For he received him up in the clouds, and “we shall be caught up in the clouds.” Do you see how great is the honor? And as he descends, we go forth to meet him, and, what is more blessed than all, so shall we be with him.”

[St John Chrysostom, Homily 8 on First Thessalonians].

At the same time, St Gregory of Nyssa understood the ‘taking up’ [ἁρπάζω] of the faithful as the means of our participation in like manner with the ascension and descent of Christ, recalling the words of St Paul:

For that which has taken place in Christ’s humanity is a common blessing on humanity generally. For we see in him the weight of the body, which naturally gravitates to earth, ascending through the air into the heavens. Therefore, we believe according to the words of the apostle, that we also “shall be caught up in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air.” Even so, when we hear that the true God and Father has become the God and Father of Christ, precisely as the firstfruits of the general resurrection, we no longer doubt that the same God has become our God and Father too. This is true inasmuch as we have learned that we shall come to the same place where Christ has entered for us as our forerunner.

[St Gregory of Nyssa, On the Resurrection of Christ, 46.617B–620A]

St Gregory seems to allude here, to the words of the angels at the ascension:

“Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven.”

[Acts 1:11]

Implying that, as the apostles witnessed his ascend to the right hand of the Father, so too shall the faithful witness his descent. And we, having been made anew in him, when we meet him at his coming, shall ascend in like manner.

Far from novel or allegorical, the Fathers interpretation is rather a clear and literal interpretation of the semantic range of ἀπάντησις in the immediate context of Paul’s letter to the Thessalonians. Indeed, we see this also throughout the Scriptures:

“And Samuel stood and departed from Gilgal to go on his way, and the remnant of the people went up after Saul to meet [εἰς ἀπάντησιν] his army coming from Gilgal to Gibeah of Benjamin.”

[1 Kgdms 13.15]

“Trypho sought to become king over Asia and put on the crown and stretched his hands upon Antiochus, the king. And he was afraid ⌊lest⌋ Jonathan should not allow him and ⌊lest⌋ he should fight against him. So he sought a ford in order to capture and kill him; and departing, he went to Beth-shan. And Jonathan went out to meet him [εἰς ἀπάντησιν αὐτῷ] with forty thousand men selected for battle, and they went to Beth-shan.”

[1 Macc 12.39-41]

“Then Tobit went out to meet [εἰς συνάντησιν] his daughter-in-law at the gate of Nineveh, rejoicing and praising God. Now those who saw him as he was walking to the gate were astonished because he could see. And Tobit gave thanks before them because God had been merciful to them.”

[Tob 11.16-17]

The same is found in the New Testament:

“…at midnight there was a cry, ‘Here is the bridegroom! Come out to meet [εἰς ἀπάντησιν] him.’ Then all those virgins rose and trimmed their lamps… and the bridegroom came, and those who were ready went in with him to the marriage feast, and the door was shut…

[Matt 25.6-10]

“…the brothers there, when they heard about us, came as far as the Forum of Appius and Three Taverns to meet us [εἰς ἀπάντησιν]. On seeing them, Paul thanked God and took courage. And when we came into Rome, Paul was allowed to stay by himself, with the soldier who guarded him.”

[Acts 28.15]

The word is used, almost in all contexts to refer to the meeting of a King, or else a dignitary. It is indeed a distinctly militarial term.

It is within this context that we may draw all things together - Far from a ‘secret’ coming of the Lord, by which he may ‘snatch away’ his church, this is a glorious and triumphal event ‘at the consummation of the ages’. At the trumpet call of the archangels, at the coming of Michael and his hosts [Dan 12.1], at the coming of the King, Christ our God, the dead and the living, the faithful from ‘the four corners of the earth’ [Matt 24.31] shall be taken up to meet the hosts of the King as he descends to rule upon the earth [Apoc 19.11–14]. The wicked, having been ‘taken’, and delivered unto judgment, shall be no more, and the saints shall be ἁρπάζω ‘caught up’ into the glory of the coming King, and shall reign with Christ upon the earth. And they shall enter into the great gates of city of the new Jerusalem, the new creation [Apoc 21.1-8; 22.14], and rule with him, unto ages of ages [Apoc 21.3; 1 Thess 4.17].

Conclusion

It is clear then, that there is little room in this interpretative framework for any of the claims of the dispensationalist rapture. There is no grounds, biblically, for a secret and sudden taking of the Church, one by which they may escape tribulation, and await the coming of the Lord and the resurrection. Indeed, such a framework runs directly against the (rather limited and opaque) depictions of the final day and the coming of the Lord, as it is depicted in the Scriptures, and interpreted by the Fathers.

But what of the relationship of this ‘doctrine’ (as we may indeed call it) to the millennium? Surely this is very backdrop against which the rapture is necessary. For the rapture is intrinsically connected, within the dispensationalist framework, the the ‘great tribulation’, consummating in the ‘millennial reign’ of Christ for a literal thousand years. Now that we have understood the correct context, and therefore interpretation of the coming of the Lord, and his meeting with the Church, how then are we to interpret that clear passages of the reign of the Lord and his saints?

We shall examine this in the next article.

Thomas D. Ice, “The Rapture in Pseudo-Ephraim”, Liberty University, (2009): 4.

Paul J. Alexander, “The Diffusion of Byzantine Apocalypses in the Medieval West and the Beginnings of Joachimism,” in Prophecy and Millenarianism: Essays in Honour of Marjorie Reeves, ed. Ann Williams (Essex: Longman, 1980).

Thomas D. Ice, “A Brief History of the Rapture”, Liberty University, (2009): 1-2.

It should also be noted that there are also some passing references in literature published by proponents of the Reformation. I have not listed these, however, due to the overwhelming lean within many of the radical groups associated with the reformation, toward a highly sensationalized eschatology. This is not representative of the broader Apostolic traditions of the Church, but was instead an example of isolated, extremist fervour. What’s more, these claims do not line up with most dispensationalist views today, and thus noting them in detail would be unfruitful. See; Ice, “A Brief History of the Rapture”, 2-3.

We will discuss these topic further in a forthcoming article.

Love this!

Thanks for the article! I completely agree with your analysis and was not aware of the (few) early views of a pre-trib rapture. It might be better to say that a pre-trib rapture was popularized through the Scofield Reference Bible.