I have written this article in preparation for Holy Week. Much of the scholarly material, particularly relating to the patristic quotations and research on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, come from Theresa Rice’s excellent article in the Church Life Journal.1 I was also inspired by the post of J. M. Robinson, who sparked my initial interest in this topic. I am indebted to both for this present work.

The Place of the Skull

At the end of the records of the trial and execution of the Lord, each evangelist mentions, in virtually identical language, the place the Roman’s called Calvariæ and the Jews ‘Golgotha’ - ‘the Place of the Skull’, as the location of the crucifixion [Matt 27:33; Mark 15:22; Luke 23:33; John 19:17]. . This is important. If you read the gospels, you will notice that they tend to differ on some points at various times, each author providing his own take, or perhaps highlighting a specific theological element of the story he is recording. But the fact that all four make note for us the reader, that the place of the death of Christ was ‘the Place of the Skull’ must therefore mean that all of them agreed on its importance.

We might ask the question – why? As far as many are concerned it often seems to be an inconsequential detail. At the least, some relevant topographical information, or perhaps, as some might view it, the key to finding the ‘true place of the crucifixion’ and therefore an important archaeological clue.

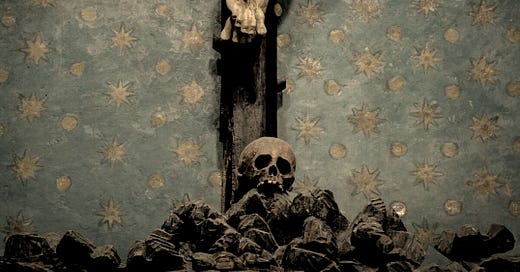

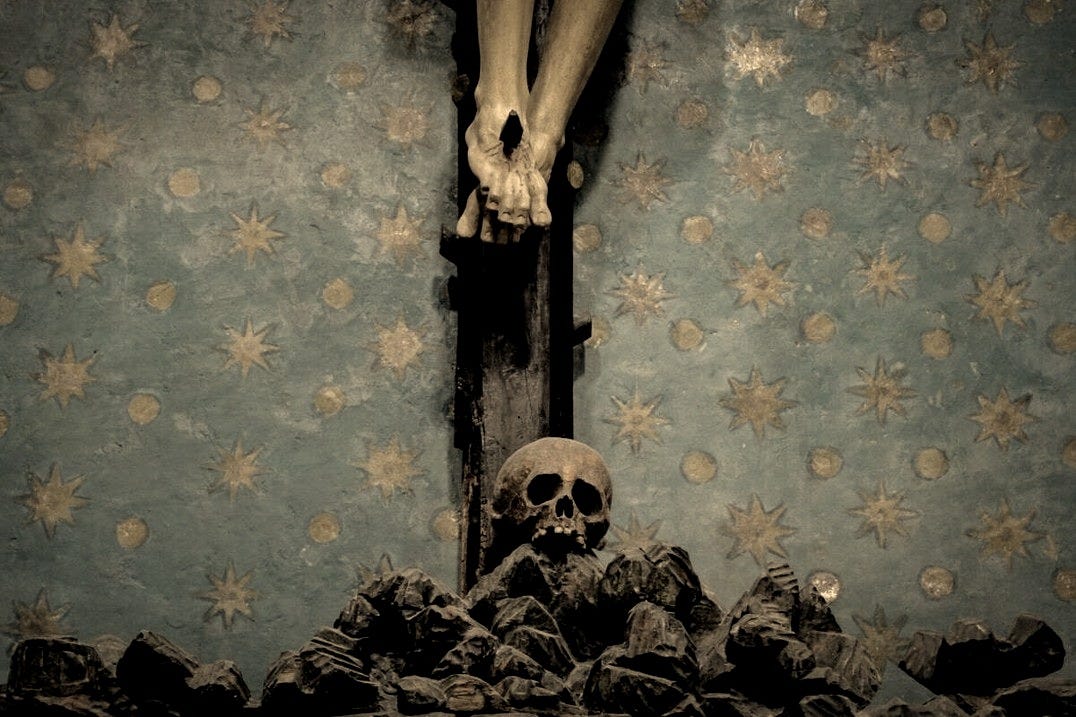

But there is, and has been for a long long time, another interpretation of its importance, one that is rich with theological symbolism and importance. One which can be found hidden in plain sight in many byzantine and medieval iconographic depictions of the Passion:

Notice that little skull under the cross? Why is that there?

The Bones of Adam

Since the third or fourth century, tradition has held that the location of the crucifixion was known as ‘Golgotha’ - ‘Place of the Skull’, because beneath the hill side was the burial place of the first man, Adam. As the story goes, upon his death, the blood of Christ, dripping from the wood of the cross and into the soil, was received by the earth like the blood of Abel [Gen 4:11; Heb 12:24], and dripped down onto the skull of Adam himself. The blood of the Last Adam redeems that of the First Adam, thus providing a very real and visceral portrait of the words of Paul, “since death came through a human being, the resurrection of the dead has also come through a human being; for as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ.” [1 Cor 15:21].

There are many early patristic accounts that attest to this tradition. Origen, writing in the 3rd century noted that:

“…a certain “Hebrew” tradition tells that the body of Adam, the first man, is buried there where Christ was crucified, so that ‘as in Adam all die’ , just so in Christ all shall be made alive’ (1 Cor 15:22).”

[Origen, ‘Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew,’ §126]

St Jerome, writing in the fourth, says:

“Tradition has it that in this city, nay, more, on this very spot, Adam lived and died. The place where our Lord was crucified is called Calvary, because the skull of the primitive man was buried there. So it came to pass that the second Adam, that is the blood of Christ, as it dropped from the cross washed away the sins of the buried protoplast, the first Adam, and thus the words of the apostle were fulfilled: Awake, you that sleep, and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give you light [Eph 5:14].”

[Jerome, Epistle 46.3]

Epiphanius, the Bishop of Salamis wrote:

…our Lord Jesus Christ was crucified on Golgotha, nowhere else than where Adam’s body lay buried…This is probably the way the place, which means “Place of a Skull,”… Why the name “Of the Skull” then, unless because the skull of the first-formed man had there and his remains were laid to rest there, and so it had been named “Of the Skull”? By being crucified above them our Lord Jesus Christ mystically showed our salvation, through the water and blood that flowed from him through his pierced side—at the beginning of the lump beginning to sprinkle our forefather’s remains, to show us too the sprinkling of his blood for the cleansing of our defilement and that of any repentant soul; and to show, as an example of the leavening and cleansing of the filth our sins have left, the water which was poured out on the one who lay buried beneath him, for his hope and the hope of us his descendants. Thus the prophecy, “Awake thou that sleepest and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give thee light,” was fulfilled here.

[Epiphanius Panarion 46.5.6-9]

And finally, St Basil of Caesarea noted the tradition that:

…the men of the time, after depositing the skull [of Adam] in that place, named it ‘Place of the Skull’. It is probable that Noah, the ancestor of all men, was not unaware of the burial, so that after the Flood the story was passed on by him. For this reason the Lord having fathomed the source of human death accepted death in the place called Place of the Skull in order that the life of the kingdom of heaven should originate from the same place in which the corruption of men took its origin, and just as death gained its strength in Adam, so it became powerless in the death of Christ.

[Basil the Great, Commentary on Isaiah 5.141]

All sources, though they may disagree on the finer details and the pedigree of the legend, agree that the blood of Christ meeting the skull of Adam serves as a potent fulfilment of the prophecy recorded in St Paul’s letter to the Ephesians. Though it is difficult to determine exactly where this pericope comes from. There is similar wording for the LXX rendering of Isa 26:19 combined with Isa 60:1.2 St Clement of Alexandria attributed it to a “lost apocryphal work of the Lord” (Protrepticus 9.84.2) and Epiphanius attributed it to the Apocalypse of Elijah (Haer. 42.12.3). Most scholars today view it as an ancient Christian hymn.3

In her article, “The Place of the Skull: Memory and Myth in the Chapel of Adam”, Theresa Rice summarises the overall theological importance of these quotations as such:

“Ultimately, the Christian textual tradition surrounding the death and burial of Adam emerges out of a desire to interpret Scripture. In their exegesis, each of these witnesses—Jerome, Epiphanius, [Origen] and Basil—read Adam’s death in light of a central Christian claim of redemption in Christ…

Each author stresses God’s providential selection of the “place of the skull” to become the origin of life out of death. These textual witnesses suggest that rather than merely transmitting a static fact, a dynamic Christian tradition situates Adam’s bones under the Cross precisely because of what the Cross is, not for Adam alone, but for “all his descendants” who inherit both his image and his mortality.”

The Chapel of Adam

These traditions have been passed down through the history of the Church and immortalised in Christian art for… well as long as anyone can remember. But the tradition of Adam has not only been told in art, but also in stone. In Jerusalem today in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, after ascending the stairs to the right of the main entrance to the place of the crucifixion to behold the rock of Golgotha, the pilgrim may find an unassuming flight of steps back on the ground floor, (often missed as people rush to see the main attraction, the great Edicule or tomb under the massive vaulted dome) which leads down into the rock, into an unadorned and unassuming little chapel. It is quite the stark difference from the lavishly furnished area above which is built around the very rock of Golgotha. Here, in a little niche in the wall, visitors can still see the stained red rock in a crack that reaches up, all the way to the foot of the cross above. This is the chapel of Adam.

Though the Chapel has been dated to as late as the 7th century4, the presence of the tradition as early as the 3rd suggests the cultic importance of the place even before it was built, following the renovation of the church by bishop Modestus in 630.5

Strikingly, the Chapel of Adam seems to have been utilised liturgically early on in a way that mirrors the theological traditions connecting the death of Adam and the resurrection. A contemporary account from a pilgrim notes how:

Towards the east, in the place that is called in Hebrew ‘Golgotha’, another very large church has been erected. In the upper regions of this a great round bronze chandelier with lamps is suspended by ropes and underneath it is placed a large cross of silver, erected in the selfsame place where once the wooden cross stood embedded, on which suffered the Saviour of the human race. Now in this church, beneath the place of the Lord’s cross, there is a grotto cut out of the rock where sacrifice is offered on an altar for the souls of certain privileged persons. Meanwhile their remains are laid out in the court before the door of this church of Golgotha, until such time as the holy mysteries for the deceased are completed.

[Adomnan, De Locis Sanctis 1:5.2]

This ‘small grotto cut out of the rock’ is without a doubt the Chapel of Adam. What’s more, the offering of the eucharist in the chapel for the holy departed shows vividly the connections made between the place of Adam’s burial, the salvific work of the Cross of Christ and the hope of the resurrection. As Rice explains:

…the burial place of Adam reaches its fullest instantiation as liturgical site of commemoration and intercession…the liturgical use of the space expresses the same instinct which motivated the narrative in the first place (as we saw in Jerome, Epiphanius, and Basil): confidence that the Cross brings life out of death for all humanity.

The liturgical use of the space proclaims the renewal of the human race in Christ: the corpse proclaims the mortality inherited from Adam, while the prayers for the dead underneath the site of the Crucifixion proclaim Christ’s life-giving transformation of that mortality. The liturgy effects and makes present the life-giving power of the Cross: the location merely intensifies what all liturgy effects.

Thus… the chapel finds its truest expression in the liturgical use—entrusting the dead to the redemptive mercy of Christ in the very place where his life-giving blood had stained the rocks.

The preservation of the tradition of Adam’s skull beneath the cross, both in scriptural interpretation, and architectural and liturgical expression, speaks to the powerful reversal of death in the crucifixion of Christ. ‘As in Adam, all died, but in Christ all live’, [1 Cor 15:22] and this reality is know where more powerfully expressed than in the symbolism of the skull of Adam himself, sprinkled with the blood of the Lamb.

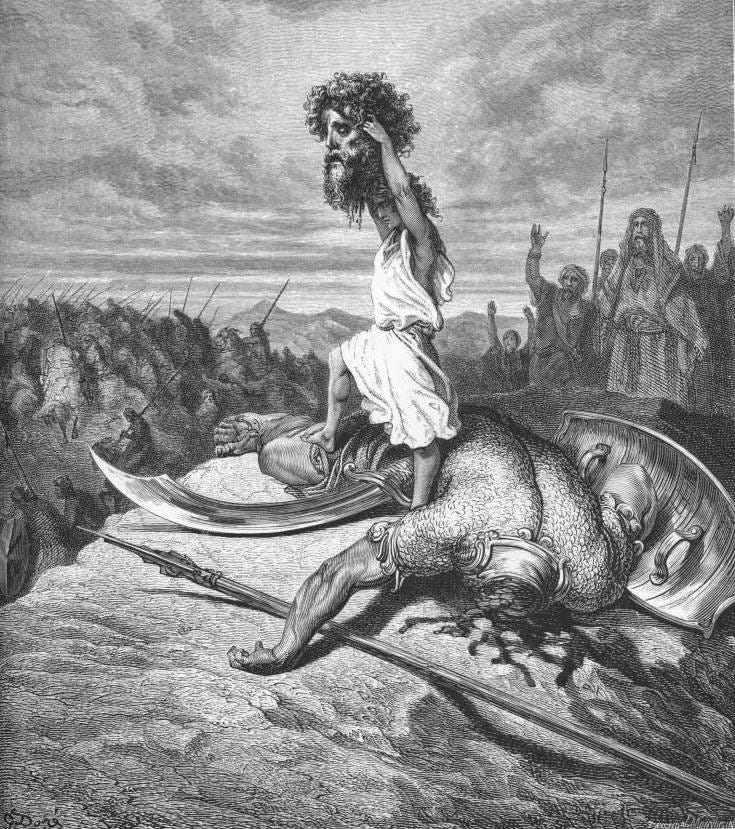

The Skull of Goliath

Yet there is another tradition, one which links the name ‘Golgotha’ to another episode of Scripture, and a figure who is of equal importance to the messianic portrait of Jesus. According to this second view, the ‘Place of the Skull’ was named as such due to its relation to the burial of the head of none other than ‘Goliath’, by the anointed King David, upon his defeat and decapitation of the Philistine giant. We know from Scripture that David brought the head to Jerusalem:

“So David prevailed over the Philistine with a sling and a stone, striking down the Philistine and killing him; there was no sword in David’s hand. Then David ran and stood over the Philistine; he grasped his sword, drew it out of its sheath, and killed him; then he cut off his head with it….

David took the head of the Philistine and brought it to Jerusalem; but he put his armor in his tent.”

[1 Sam 17:50-51, 54]

In support of this tradition, some have suggested that the Hebrew ‘Golgotha’ is a corruption and blending of the name of Goliath גָּלְיָ֥ת גַּ֑ת ‘Golyat Gat’ – ‘Goliath of Gath’ [1 Sam 17:4]. Others have suggested that the name comes from גַּל גָּלְיָ֥ת ‘Golgolyat’ - ‘heap’ or ‘pile of Goliath’ in reference to the mound built around his giant skull in order to bury it.

While there is not nearly as strong of a presence of this interpretation within early Christian tradition, which almost universally favours the interpretation of the skull of Adam (for obvious christological reasons), there is certainly several typological connections bolster it’s theological weight.

Just as Christ is the New Adam, so too is he the Greater David. Hailed as “the Son of David” by lepers [Lk 18:38], and by the crowds at the triumphal entrance [Matt 21:9], Jesus fulfils the Davidic expectation of the Messiah [Matt 1:1-16; 22:42]. Like David, who was anointed by Samuel before he faced the Giant [16:12-13], Christ too was anointed by Mary at Bethany, on his way to the holy city [Matt 26:6-13; John 12:1-8]. Both, interestingly, at the time of the their anointing, are not recognised by the people of Israel as the true King. Following David’s defeat of Goliath the people of Israel begin to waver in their allegiance to Saul [1 Sam 18:6-9], an eventually prefer him as King [1 Sam 18:16; 21:11] and it is only at his crucifixion, that Christ is recognised as ‘King of Jews’ and the ‘Son of God’ [Mark 15:18; John 19:19-22; Matt 27:54].

There is also theological importance to the image of David killing the giant with a blow to the head, and of course, beheading him. Recall that God had promised serpent at the fall:

“I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel.”

[Gen 3:15]

The story of David and Goliath undoubtedly reflects this messianic imagery, and is positioned by the author of 1 Samuel as a typological fulfilment of the prophecy. The depiction of Goliath is quite telling:

He had a helmet of bronze on his head, and he was armed with a coat of mail; the weight of the coat was five thousand shekels of bronze.

[1 Sam 17:5]

Goliath wears a helmet of נְחֹ֙שֶׁת֙ nakhoshet ‘bronze’ which uses the same Hebrew words as the word נָּחָשׁ֙ nakash ‘serpent’ [like in Genesis 3]. The description of his armour uses the Hebrew word קַשְׂקֶ֫שֶׂת ‘qashqeshet’ used to describe for ‘scales’ of a unclean fish or snakes [Lev 11:9-12] and to describe the dragon-like Pharoah [Ezek 29:4] reminiscent of Leviathan [Job 41]. He is also, of course, a Nephilim, descendant of the mighty giants from before the flood, who were the evil offspring of angels and women [Gen 6:1-4; 1 En. 7]. Goliath thus symbolically and typologically represents the serpent in Eden, the great dragon, the unclean monster, the spiritual enemy of humanity. David defeats this serpent giant by ‘striking’ his head, causing him to fall into the dust (just like the serpent is cursed to eat the dust) and ‘cuts off’ his head, just as we read in Genesis.6

Christ accomplished this same victory over Satan himself. As he is about go up to Jerusalem, St John tells us how Christ says to his disciples:

Now is the judgment of this world; now the ruler of this world will be driven out. And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.” He said this to indicate the kind of death he was to die.

[John 12:31-33]

Christ’s ‘lifting up’ is his crucifixion, and it is through his death on the cross that the ‘ruler of this world’, who is Satan, is ‘driven out’. Like his ancestor King David, Christ smashes the head of the serpent and cuts off the head of the giant at the ‘Place of the Skull’ of Goliath himself.

***

With all this before, we may be tempted to ask - but which tradition is true?

Why not both?

Both traditions shed important light on the deeper theological meaning of the crucifixion, and give us pause to consider why the gospel authors all go out of their way to mention the importance of the location of Golgotha for the victory of the Lord.

Christ is the New David, who has defeated the great Enemy of God’s people, cutting of his head, and stripping him of his power of humanity [Col 2:15]. Likewise, he is the New Adam, whose blood shed on the cross has redeemed all of the race of Adam. The hope of resurrection, the victory over death and the promise of deliverance from spiritual enemies serve as the central accomplishments of the saving work of Jesus on the Cross.

And all of this, in one small detail, this seemingly insignificant location, this ‘Place of the Skull’ which contains within it some of the richest themes of the Christian faith, the glorious and saving work of our Crucified King, the Son of David, the True Adam.

Theresa Rice, “The Place of the Skull: Memory and Myth in the Chapel of Adam” Church Life Journal (November 3, 2023).

Clinton E. Arnold, Ephesians: Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010), 334-335.

John Muddiman, The Epistle to the Ephesians BNTC (London: Continuum 2001), 242-243.

Shimon Gibson, Joan E. Taylor, Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre Jerusalem: The Archaeology and Early History of Traditional Golgotha, (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1994), 60.

Joan E. Taylor, Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish–Christian Origins (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1993),122–134.

For further treatment on these themes, see Brian A. Verret, The Serpent in Samuel: A Messianic Motif (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2020).