Keeping the Ancient Boundaries - Pt. 2

Authority, Mystagogy and Relevance in the Traditions of the Church

This is the second part of my article on the relevance of apostolic tradition in Christianity. If you’d like to read the first part, you can find it here.

Catholicity, Orthodoxy and Truth

As we saw in our previous article, for the apostles and early fathers, the traditions of the Church encompass within them the very substance of the Church. Founded upon the cornerstone of Christ and established upon the traditions of the apostles (Eph 2:22), the Church is thus, as St Paul states, “the pillar and bulwark of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15). As such, truth is to be found only within the traditions preserved in the Church:

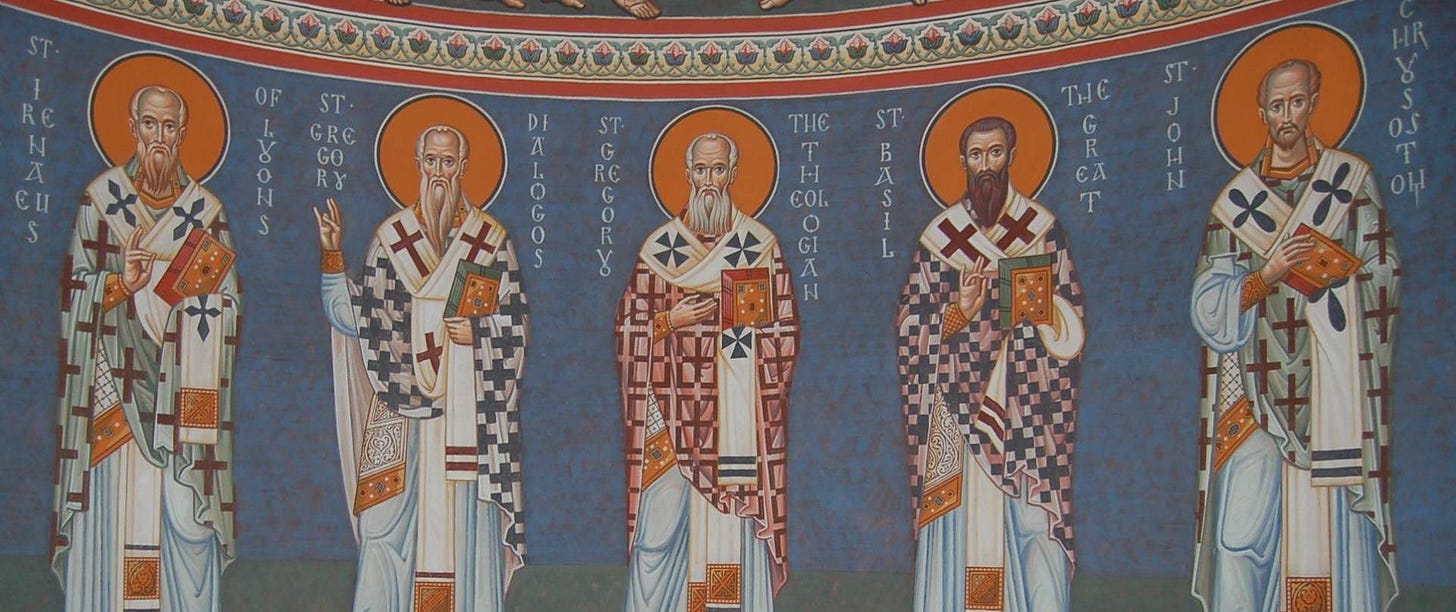

It is within the power of all, therefore, in every Church, who may wish to see the truth, to contemplate clearly the tradition of the apostles manifested throughout the whole world

[St Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3.3.1]

As truth is universal, so too is the Church herself universal or catholic. As we confess in the Nicene Creed, “I believe…in One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church” - the Church’s apostolicity is the source of her catholicity. As St Irenaeus wrote:

The Church…has received from the apostles and their disciples this faith…although scattered throughout the whole world, yet, as if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it. She also believes these points [of doctrine] just as if she had but one soul, and one and the same heart, and she proclaims them, and teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she possessed only one mouth.

[St Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1.10.1]1

Or as Tertullian noted:

“[The apostles] founded churches in every city, from which all the other churches, one after another, derived the tradition of the faith, and the seeds of doctrine, and are every day deriving them, that they may become churches. Indeed, it is on this account only that they will be able to deem themselves apostolic, as being the offspring of apostolic churches. Every sort of thing must necessarily revert to its original for its classification. Therefore the churches, although they are so many and so great, comprise but the one primitive Church, [founded] by the apostles, from which they all [spring]. In this way, all are primitive, and all are apostolic, while they are all proved to be one in unity”

[Tertullian, Prescription Against the Heretics, 20. ]

Furthermore, the Church’s catholicity is testament to her orthodoxy. The preservation of the established tradition is, as we hinted at before, what guards the Church from error:

“…as the sun, that creature of God, is one and the same throughout the whole world, so also the preaching of the truth shines everywhere, and enlightens all men that are willing to come to a knowledge of the truth. Nor will any one of the rulers in the Churches, however highly gifted he may be in point of eloquence, teach doctrines different from these (for no one is greater than the Master); nor, on the other hand, will he who is deficient in power of expression inflict injury on the tradition. For the faith being ever one and the same, neither does one who is able at great length to discourse regarding it, make any addition to it, nor does one, who can say but little diminish it.”

“…what we are, that the Apostles were, and they taught what they received from Christ. Therefore, whatever is contrary to their teaching must be rejected.”

[St Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1.10.2]

In this way, the traditions of the apostles, past down and constitutive of the traditions of the Holy Fathers also, serve as the ‘ancient boundaries’ (recalling the words of Proverbs 22:28) by which the Church remains true to Christ. As St John of Damascus states:

“We do not change the everlasting boundaries which our Fathers have set, but we keep the tradition just as we received it.”

[St John of Damascus, Three Treatises on the Divine Images, 69.]

Tradition and Scripture

But what of the place of Scripture? Should we not say rather that it is Scripture that keeps the Church from error? Is it not the revelation of God that unites the Church? Indeed! But to what do we measure the Scriptures? To what do we render an account of our interpretations and our teaching? To the apostolic tradition of the Church. As St Peter warns his flock:

you must understand this, that no prophecy of scripture comes about from one’s own interpretation, for no prophecy was ever produced by the will of man, but rather men carried along by the Holy Spirit spoke from God.

[2 Pet 1:20-21]

The Scriptures cannot be interpreted outside of the witness of the Church whose authority, as we have seen, is derived from the Spirit Himself. Such a question fails to realise that it was the apostolic tradition that both shaped the scriptures, and came to be preserved within them. Scripture can never read in a vacuum (or as a matter of personal interpretation, as Peter warns). Rather, it is the Apostolic witness and tradition that enables the Church to interpret Scripture correctly. As St Cyril of Jerusalem, writing in about AD 350, wrote:

“…the Church alone has the full and accurate knowledge of the Scriptures, because she has received them from the Apostles….

[St Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures, 5.12.]

Indeed,

“We do not deliver to you clever arguments, but what we have been taught by the holy Apostles, and what we have received from the Scriptures. Do not believe me because I tell you these things, unless you receive the proof from Holy Scripture.

Yet he clarifies:

At the same time… do not reject anything that is handed down to you, even if it is not found in the Scripture, since we have received it by tradition.”

[St Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures, 6.29.]

While everything is to be “proofed” from the Scriptures, St Cyril nevertheless elevates the holy tradition of the apostles as an authority in and of itself. Thus, for the Church to truly remain the “pillar and bulwark of truth”, she must utilise the authority of Scripture within the boundaries of the Apostolic Tradition. The two go hand in hand. As Fr. Joseph Lucas notes,

“Holy Tradition does not represent a parallel body of information but rather an apposite extension of Holy Scripture- it would be best to say Scripture in Tradition, not and. One does not exist outside the other.”2

There is thus a synergia [‘working together’] between the Scriptures and the Church. As Kalantzis writes:

“there is a synergia, a spirit of organic unity between the Scriptures and the Church whose life, liturgy, preaching, teaching, spiritual formation, and theology it shapes and forms. This synergistic relationship is based on the recognition that the Bible is not sui generis [of its own kind/unique] but is born and shaped within the Ekklesia [Church], the community of faith to which it is addressed and by which it is received.”3

And thus, as Stylianopoulos notes:

“Scripture is only useful to the hearer when it is spoken [in the presence of] Christ, when it is presented with the Fathers, and [when] those who are preaching do not introduce it without the Holy Spirit.”4

The role of tradition for scriptural interpretation thus cannot be relegated to a historical reality, any more than the event of its revelation, but must instead be recognised as “the living memory of the Church”.5 Just as God’s self-revelation in the Scriptures is an on going pneumatic reality, so too is its interpretation within the Church and her tradition.

The Mysteries of Christ

Having established the place of tradition within the Church, and its relationship to Holy Scripture, I want to add a couple of final thoughts regarding its mystogogical purpose. St Paul described the teachings of the apostles as μυστήριον mysterion ‘mysteries’:

Among the mature we impart wisdom, although it is not a wisdom of this age or of the rulers of this age, who are doomed to pass away. But we impart a mystery, the hidden wisdom of God, which God decreed before the ages for our glory…

[1 Cor 2:6-7]

The mystery St Paul speaks of is of course, the salvific revelation of Jesus Christ (Col 1:26-27; Eph 3:4-6). But within this is also contained the holy mysteries of the Church, the life of Christ in her. The apostolic tradition holds within it the roots of the holy mysteries of the Church, the foci of her sacramental substance. St Basil attests to the preservation of such mysteries in the apostolic teachings:

"Of the dogmas and messages preserved in the Church, some we have from written teaching, others we have received delivered to us 'in mystery' by the tradition of the Apostles. Both have the same force."

[St Basil, On the Holy Spirit, 26.]6

As the logos, the very Word of God, Christ had taught with authority (Matt 7:29) and revealed the hidden things of God. Christ had given these teachings to his apostles, “To you has been given the secret [μυστήριον -mysterion] of the kingdom of God” (Mark 4:11) and bestowed on them his authority which they then passed down to the Church (cf. John 20:21-23).

St Ignatius spoke of how these mysteries consisted not just of ecclesial matters but also of cosmic revelations - “celestial secrets and angelic hierarchies and the dispositions of the heavenly powers and much else both seen and unseen …” (St Ignatius, Trallians, 5). St Paul himself, was granted “visions and revelations of the Lord” (2 Cor 12:1) and was “caught up to the third heaven” and “into paradise”, where he “heard things that cannot be told, which man may not utter” (2 Cor 12:2-4).7

While such mysteries were not recorded explicitly in Scripture, early fathers understood the necessity of these oral traditions of the apostles for the heart of the faith.8 As St Basil puts it:

“The unwritten traditions are many… and they possess so great a strength for the mystery of our religion”

[St Basil, On the Holy Spirit, 67.]

It is through the deposit of the apostles that the Church receives these mysteries as the new temple of God, and a holy priesthood (1 Pet 2:5-9). Many of the early fathers liken the mysteries of the Church to the mysteries associated with the levitical priesthood and the temple.9 This is also apparent in St Paul’s homily to the Hebrews (Hebrews 7-10) and similar works such as the Epistle of Barnabas (6:23; 8:1-7; 11:1-12; 12:5-6; 16:1-10). As St Ignatius puts it:

“The priests of old, I admit, were estimable men, but our own High Priest is greater, for he has been entrusted with the Holy of Holies. And to him alone are the secret things of God committed. He is the doorway to the Father, and it is by him that Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and the prophets go in, no less than the apostles and the whole Church; for all these have their part in God’s unity”

[St Ignatius, To the Philadelphians 9.]

Through their witness and teachings, Christians become “initiates of the same mysteries” (St Ignatius, Ephesians, 12), as the apostles, and as such, may “…enter in, through the tradition of the Lord, by drawing aside the curtain” (St Clement, Miscellanies 7.17.).

Furthermore, this revelation of the mysteries of Christ to the apostles and its preservation in the Church is a process intrinsically connected to the role of the Holy Spirit. As Christ promised to his disciples:

“ I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth; for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears he will speak, and he will declare to you the things that are to come.”

[John 16:12-13]

We see the Holy Spirit intrinsically involved in Christ’s (rather sacramental) ordination of the apostles when he appears to them in the upper room:

Jesus said to them again, “Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, so I send you.” When he had said this, he breathed on them and said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.”

[John 20:21–23]

St Paul confirms that the revelation of such mysteries to the Apostles was indeed the work of the Spirit:

“…we have received not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit who is from God, that we might understand the things freely given us by God. And we impart this in words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit, interpreting spiritual truths to those who are spiritual.”

[1 Cor 2:12-13]

The apostolic deposit and its outworking in and through the Church provides the vital link to the Church’s mystical substance, the tangible sign of the spiritual reality brought about by the indwelling of the Spirit of God in the Church, as both the new temple, and the new priesthood. The apostolic tradition is thus also the depositum mysterium, or depositum sacramentalis [sacramental deposit]. And it is through this that the resurrected life of Christ is made available in the mysteries of the Church, and through them, that the life of the new creation in Christ is given to the world.10

Ever Ancient, Ever New

So why is this important?

We live in a world which is constantly in flux and changing, chaotic and unmoored. There is no catholicity to be found in our modern smorgasbord of culture and religion, and thus there is no one truth, no observable and definable orthodoxy.

Yet the catholicity and orthodoxy of the Church’s traditions “delivered once and for all to the saints” (Jude 3) remains steadfast. For this reason, the claim of the Church’s traditions to be not merely ‘human tradition’ (cf. Mark 7:13) , but rather the very ‘words of God’ in Christ through the Apostles stands as a firm anchor (Heb 6:19), one to which we can hold, so that we may not be “tossed to and fro and blown about by every wind of doctrine” (Eph 4:14).

As George Florovsky put it:

We are living now in an age of intellectual chaos and disintegration… modern man has not yet made up his mind, and the variety of opinions is beyond any hope of reconciliation… the only luminous signpost we have to guide us through the mental fog of our desperate age is just the "faith which was once delivered unto the saints." 11

The modern church thus needs the apostolic deposit as much as the ancient church needed it (if not more!) Without it, we cannot affirm the creedal statements of ‘one catholic and apostolic church’ founded on Christ and imbedded within the reality of the ‘communion of saints’. Without it, the Church is robbed of her mystagogical essence and her apostolic witness, and authority, all of which are issues which the modern church is awash with. If we are to remedy this, then we must look to the past, to the origin of the Church, and to those who have come before. As Jeremiah admonished Israel, we must:

look, and ask for the ancient paths, where the good way lies; and walk in it and find rest for [our] souls.

[Jeremiah 6:16]

We must recognise that we are not at liberty to re-invent the Church of Christ, but rather must subject ourselves to the ancient boundaries of our fathers, the boundaries that have, and will continue to safe guard the depositum juvenescens ‘living deposit’ of the faith that is ever ancient and ever new.

The significance of the Apostolic Tradition for the Church, therefore, cannot be understated.

It is the depositum fidei, the central reality of the Church’s identity. It is the depositum juvenescens, the vital lifeline through which the Church, rooted on the cornerstone of Christ himself, flourishes and by which the synergia of both tradition and Scripture gives to the Church her authority. It is the depositum mysterium, the life of the world, through the ministry of the Church. The reality of Christ himself, made manifest and present, as the head of his body, and the Bridegroom of the Bride.

The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Cox. Vol. 1. (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 331.

Fr. Joseph How to Read the Holy Fathers: A Guide for Orthodox Christians, (Indiana: Ancient Faith 2024),

George Kalantzis, “Scripture in Eastern Orthodoxy: Canon, Tradition, and Interpretation”, in, The Sacred Text, (Gorgias Press, 2010), 201.

Theodore G. Stylianopoulus, “Orthodox Biblical Interpretation,” in Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation (Nashville: Abingdon, 1999), 2:227.

Sergius Bulgakov, The Orthodox Church (Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1997), 10.

Margaret Barker, Temple Mysticism, (London: SPCK, 2011), 4-5, 10.

We might also note the other charismatic visions and experiences of apostles such as St Philip and St Peter in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 8:39; 10:9-16).

Margaret Barker, Temple Themes in Christian Worship (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), 1-3.

See Barkers treatment in: Margaret Barker, The Hidden Traditions of the Kingdom of God (London: SPCK, 2007), 33-36.

Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy, (New York: SVS, 2018).

George Florovsky, Bible, Church, Tradition: An Eastern Orthodox View, (Belmont: Nordland, 1972), 10-11.