In Hebrews 9:1-4, St Paul outlines how the old covenant set out the δικαιώματα λατρείας ‘regulations for worship’ for the ἅγιον ‘sanctuary’. He has in mind the concluding chapters of Exodus wherein in God outlines to Moses the exact plans of the tabernacle and the regulations of worship therein (Ex 25-40), which are to based upon “the pattern revealed to you on the mountain” (Ex 25:40).1

I have discussed at length the concept of heavenly participation in the liturgy of the Church. But what about the furnishings of the worship space? Some may take Paul’s words to mean that the regulations of the old covenant have passed away with the law, and as a result, Christian worship today is not founded upon the structures, forms, and types that we find in therein. “This is the new testament” they might say, “all that was for the Old Testament, and need not concern us today.” Certainly, aspects of the law having been found old and worn out have faded away (Heb 8:13) . But this does not mean that the worship of the new covenant is no less regulated, or patterned, on the eternal types revealed in the old.

This truth was apparent to the Fathers, who understood the worship and services of the temple as pointing forward, and thus informing, the worship of the Church:

“All these things which were figuratively done in the tabernacle or temple or priesthood or sacrifices or feast-days, were predictions of future things pertaining to the Church.”

[St Augustine City of God 15.2]

“If you come to the church of God, you will find the high-priest who is Christ, the sacred altar, the true purification. You will find the Levites and the priests, and the whole order of ecclesiastical rank.”

[Origen Contra Celsum 8.17.]

So, in this article, while St Paul states that “of these things we cannot speak now in detail” (Hebrews 9:1-5), I will take the que of the Fathers, and presume to dive a little deeper into how the furnishings of the tabernacle inform Christian worship.

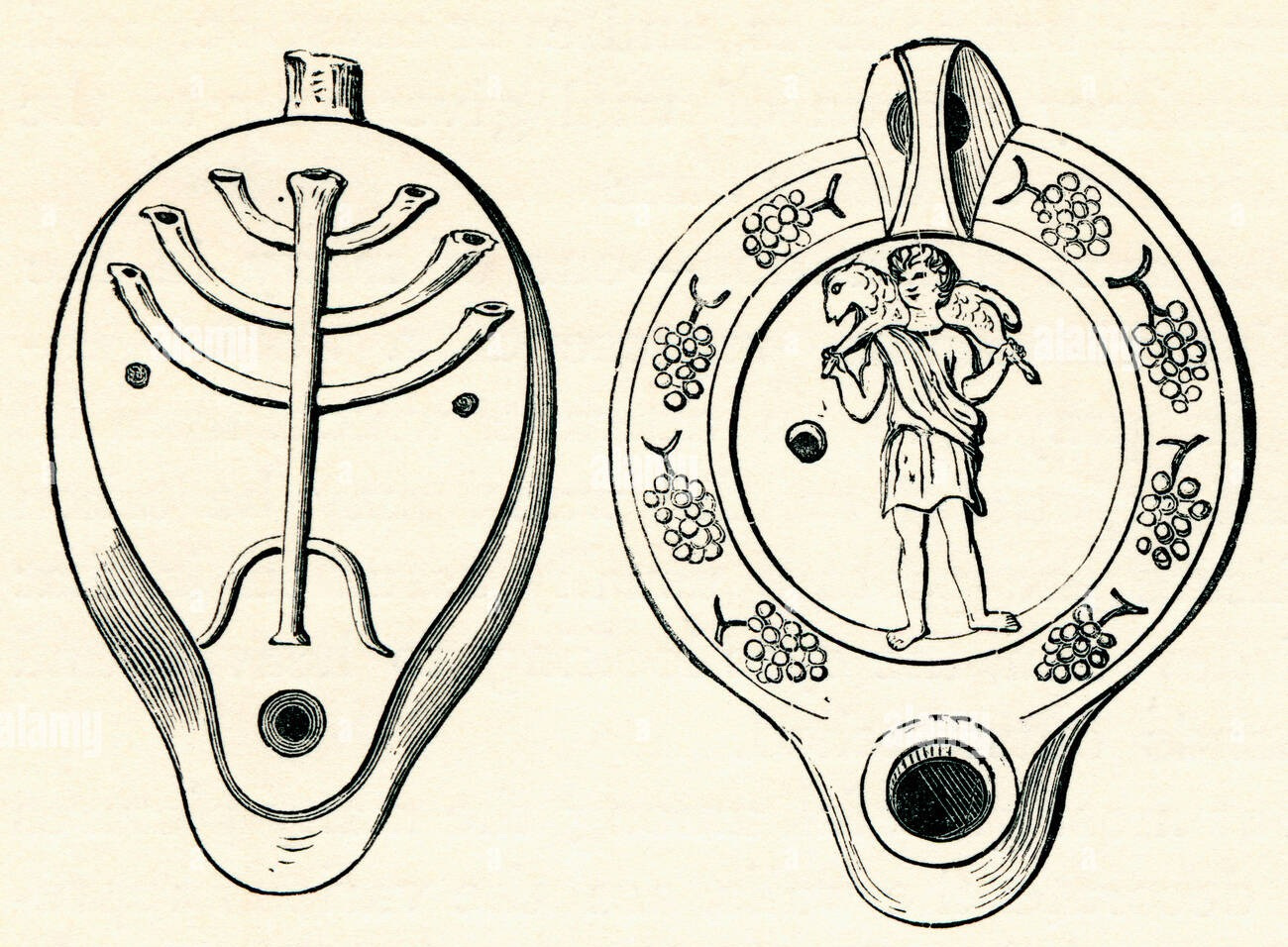

The Lamps

The λυχνία ‘lampstand’ mentioned by Paul is the great מְנֹרַ֖ת ‘menorah’, of the tabernacle (Ex 25:30; 1 Kgs 7:48-50; 1 Macc 4:48-51). The craftsmanship of the lampstand, with its seven bowls shaped as almond branches (Ex 37:17-24) recalled the seven ‘days’ of the creation week (Gen 1:3-31), the planets (Josephus, Ant. 3:179-183; Wars 5:217-218), the luminaries of the heavens (Gen 1:14-16) and the tree of life in the Garden of Eden (Gen 2:9). The burning lamps recall also the burning bush (Ex 3:2) and the pillar of fire (Ex 13:21). The great lamp thus served as a symbol of the presence of God, his creative power, and his protection of Israel. It burned perpetually before the veil, alongside the altar of incense, “as an image of His abiding Presence in the midst of His people. As the lights never went out, so God would never abandon His people.”2

In Zecheriah’s prophecy, the lampstands serve both as images of the God’s presence and of his anointed Messiah (Zech 4:2-3; 10-14). In the Apocalypse of St John, the risen and glorified Christ appears to the visionary in the midst of the lampstands (Rev 1:12-16), which serve also as an image of the Church (Rev 1:20).

The practice of lighting candles, and the liturgical use of candles and lamps is an ancient practice in Christianity. Not simply a practicality, but also as a symbolic reminder of the presence of Christ, his glory, and the hope of resurrection, and as a physical representation of the scriptural witness of Christ as the “light of the world” (John 8:12)

“Candles are to be lighted during the reading of the Scriptures and prayers...”

[Apostolic Constitutions 8.4]

“Just as lamps are lit and placed in the church to dispel darkness, so the truth of Christ enlightens the hearts of believers.”

[St Ambrose On the Mysteries 2.8]

The light of the gospel shines forth from the Church, as the menorah illumined the tabernacle - symbolising not only Christ’s presence amongst the lampstands of his Church, but also his victory over death, a sign that “the light has come into the world, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5).

The Table and Bread of the Presence

The πρόθεσις τῶν ἄρτων ‘presented bread’ or ἄρτους ἐνωπίους ‘bread of the presence’ (Ex 25:30) and τράπεζα ‘table’ mentioned by Paul can be found in Leviticus 24:

“…you shall take finely milled flour, and you shall bake with it twelve ring-shaped bread cakes: each one shall be two-tenths of an ephah. 6 And you shall place them in two rows, six to the row, on the pure gold table ⌊before⌋ Yahweh. 7 And you shall put pure frankincense on each row so that it shall be for the bread as a memorial offering, an offering made by fire for Yahweh. 8 ⌊On every Sabbath⌋ he shall arrange it in rows ⌊before⌋ Yahweh continually; they are from the ⌊Israelites⌋ as an everlasting covenant. 9 And it shall be for Aaron and for his sons, and they shall eat it in a holy place, because it is ⌊a most holy thing⌋ for him from Yahweh’s offerings made by fire—a ⌊lasting rule⌋.”

[Lev 24:5–9]

The loaves of the bread of the presence were a symbol of the relationship between God and his people. It was an image of the banquet shared between God and Israel (Ex 24:1-18) – recalling the food of Eden, and its abundance (2:15-16).

Pitre notes how in Jewish tradition, the bread of the presence was understood to have miraculous properties. “After the priests took the bread out of the Holy Place, they would lay it on the “table of gold,” so that they might eat it among themselves (Mishnah, Menahoth 11:7). According to the Jewish Talmud, during the reign of one particularly holy High Priest, even a small piece of the Bread of the Presence could provide miraculous sustenance:”

“During the whole period that Simon the Righteous ministered as High Priest], a blessing was bestowed upon the ‘omer, the two breads, and the Bread of the Presence, so that every priest, who obtained a piece thereof as big as an olive, ate it and became satisfied with some eating thereof and even leaving something over.”

[Babylonian Talmud Yoma 39A]3

During the Second Temple Period, the loaves would be brought out of the sanctuary and put on display for pilgrims to see and venerate them. “They would remove the Golden Table of the Bread of the Presence from within the Holy Place so that the Jewish pilgrims could see it. When they removed the holy bread:

…[the priests] used to lift up [the table] and exhibit the Bread of the Presence on it… saying to them, “Behold, Gods love for you!

[Babylonian Talmud Menahoth 29A]

Pitre explains this ceremony as relating to the covenant. “It seems safe to suggest that the Bread of the Presence was a sign of God’s love because it was a sign of the covenant. In the Old Testament, the covenant between God and Israel is frequently described in terms of a “marriage” bond, a covenant of love between the divine Bridegroom (God) and his earthly Bride (Israel) (cf. Ezekiel 16; Isaiah 54; Hosea 1-2)… As the visible sign of this everlasting covenant, the Bread of the Presence was the visible sign of the divine Bridegroom’s love for his Bride. Perhaps that is why the priests could say to the people when they held up the bread, “Behold, God’s love for you!”4

The bread of the presence also speaks of the mystery of the incarnation. While it is often understood that the table and the loaves were named as such because they are set before God’s presence (Ex 25:30), and consumed by the priests in the presence of God (Lev 24:9), the Hebrew [לֶ֥חֶם פָּנִ֖ים] more literally means “bread of the face”. In another sense then, the bread serves as a visible sign of the face of God, the revelation of himself to his people. In God’s command for the Israelites to attend the temple services, he commands that “Three times a year all your men shall [יֵרָאֶה֙ אֶת־פְּנֵ֛י] see the face of the Lord, Yahweh, the God of Israel” (Ex 23:17; 34:23), and this was done through the showing of the sacred vessels of the temple, particularly the bread, which served as a sort of theophany for the people. As Pitre concludes then, “it seems that, for ancient Jews, the Bread of the Presence [while] not the actual face of God, [was] an earthly sign of his face.”5

Farley notes how the twelve loaves function as “a type of Christ, the Bread of Heaven, who is Himself the embodiment of Israel… the bread images both Israel and Christ [which] is fulfilled in the Church, for the Church is both Christ’s people and His Body, Christ Himself… the Eucharist expresses and fulfills this identity, for the eucharistic bread represents us and our sacrifice, and it becomes Christ Himself.”6

The Table of the Presence is the altar upon which the Eucharist is offered. Christ called himself “the bread from heaven” and the “bread of life” (John 6:35-40) and his offering of his body is the sign of the new covenant (Luke 22:19-20) the visible sign by which the priests may proclaim “behold, God’s love for you”. In the Eucharist, Christians encounter the living Christ through the medium of his incarnation in flesh and blood, the means by which we “see the face of the Lord” (Ex 34:23). The Christian offering is not the offerings of animals on the earthen altar in the outer court, but is rather the offering of fellowship within the inner sanctuary of the Temple.

The Altar of Incense

St Paul notes how behind the δεύτερον καταπέτασμα “second curtain” was the Ἅγια Ἁγίων ‘Holy of Holies’. In here, we encounter the θυμιατήριον ‘censer’ made of χρυσος ‘gold’. While this word typically denotes the censer rather than the ‘incense altar’ (2 Chron 26:19; Ezek 8:11; 4 Macc 7:11; cf. Num 16:47), the word is based on the noun θυμιάματος which means literally ‘that which is burnt’ – implying the incense altar (cf. Ex 30:1 LXX).7 While there is some discrepancy in Paul’s account as to the placement of the altar, possibly due to the vagueness of the LXX’s rendering of Exodus 37:24-28,8 the MT is clearer, stating that it was ‘before the curtain’:

You shall make an altar on which to offer incense; you shall make it of acacia wood… and overlay it with pure gold… You shall place it in front of the curtain that is above the ark of the covenant, in front of the mercy seat that is over the covenant, where I will meet with you. Aaron shall offer fragrant incense on it; every morning when he dresses the lamps he shall offer it, and when Aaron sets up the lamps in the evening, he shall offer it, a regular incense offering before the Lord throughout your generations.

[Ex 30:1-2, 4, 6-8]

The incense itself was holy, and the recipe was sacred and prohibited for anyone other than the priests:

The Lord said to Moses: Take sweet spices, stacte, and onycha, and galbanum, sweet spices with pure frankincense (an equal part of each), and make an incense blended as by the perfumer, seasoned with salt, pure and holy; and you shall beat some of it into powder, and put part of it before the covenant in the tent of meeting where I shall meet with you; it shall be for you most holy. When you make incense according to this composition, you shall not make it for yourselves; it shall be regarded by you as holy to the Lord.

[Ex 30:34–38]

The incense served a pivotal role during the central feast of Israel, the Day of Atonement, in which it screened the High-Priest from the presence of God in the sanctuary, enabling him to perform the rites:

He shall take a censer full of coals of fire from the altar before the Lord, and two handfuls of crushed sweet incense, and he shall bring it inside the curtain 13 and put the incense on the fire before the Lord, that the cloud of the incense may cover the mercy seat that is upon the covenant, or he will die.

[Lev 16:12–13.]

In general, incense served as a symbol of the prayers of the people of God, as David prayer “Let my prayer rise before you as incense (Ps 141:2). St John, in his apocalypse, has a vision of the heavenly altar, around which angels offer incense from censers, stating how “the smoke of the incense, which was the prayers of the saints, rose before God from the hand of the angel.” (Rev 8:3-4). There is a correct practice of offering incense, deviation from which is punished severely, as seen in the case of Nadab and Abihu (Lev 10:1–2; cf. Isaiah 1:13)

Incense also purifies or sanctifies people and objects. (Lev 16:12-13) In one instance, Yahweh commands Aaron to use incense in order to stop a plague by censing the people (Num 16:46-48). Incense is offered also for the purpose of veneration. It is burned before the sanctuary and offered before the ark, and the holy relics within it. (Ex 30:34–36).

Incense serves to prepare the sanctuary, symbolizing God’s acceptance of his people’s worship, both within the old, and the new covenants. In this, “the incense foreshadows Christ, the One who makes us acceptable to God.”9 As such, incense has always been a part of Christian worship, as a fulfilment of the words of Malachi that:

“in every place incense shall be offered to my name, and a pure offering; for my name is great among the nations, says the LORD of hosts”

[Mal 1:11]

It is primarily offered before the altar, as means to sanctify and prepare it for the Eucharist. In some traditions, the priest will also cense holy relics and icons or images, as well as the people themselves (who are εἰκών ‘icons’ of God, cf. Gen 1:26 LXX), as a sign of veneration and as a symbol of their prayers before God.

The Ark and Its Contents

The ark and its contents were of particular significance for the Israelites. Build as either the footstool or the throne of God (1 Sam 4:4; 1 Chron 28:2), the ark served as the central symbol of the Yahweh’s enthronement in the tabernacle (Ex 25:22). St Paul describes how the manna, the staff of Aaron, and the tablets of the law were stored within it (Heb 9:4). These were primary relics of the wilderness generation, and were symbols of the authority of the priesthood, the law, and the provision of God. Aaron’s staff had budded as a sign of God’s election of his priestly office (Num 7:1-12). The tablets of the Law had been written by Moses (Ex 34:28), after he had smashed the ones written by God himself (Ex 31:18; 32:18). The Manna was God’s main sign of provision for Israel on their way to the Promised Land (Ex 16:1-36). It was understood as being the “bread of the angels” and of heavenly origin (Ps 78:25; Wis Sol 16:20-21). Aaron preserved some of this manna as a sign for the people and set it before the ark (Ex 16:32-34). Jews in Jesus time expected this manner to return with the coming of the Messiah.

St Paul notes specifically how there were Χερουβὶν δόξης ‘glorious Cherubim’ on either end of the ark, overshadowing the ‘mercy set’ with their wings. This was symbolic of the throne chariot of God seen by later prophets (Ezekiel 1:4-10). That the Cherubim are described as δόξης ‘glorious’ by Paul indicates their connection within the divine presence (Sir 49:8; Heb 1:3; 4:16).10 Cherubim were also embroidered on the curtains of the tabernacle (Ex 26:1), and in Solomon’s temple they were gilded in gold along the walls (1 Kgs 6:29). These facts also demonstrate that the command to “make no graven image” (Ex 20:4-5 and Deut 5:8-9) clearly was not taken to refer to all images, but rather as distinguishing idols from liturgical representations and images used, and indeed, commanded, by Yahweh for the worship of the tabernacle (Ex 25:18-21). We see the same thing in many Second Temple Jewish synagogues, all of which informed seems to have informed the Christian understanding of iconography, particularly as a means of portraying physically the theology of the incarnation. For while Moses was commanded to make no image of God “for you saw no image on the mountain” (Deut 4:15), Christians have seen the face of God revealed in the Son, whom we depict in his humanity.11

The ark has often been understood within the Christian tradition as a sign of the incarnation, particularly with regards to Mary. Early Christian’s marvelled at the claim that God had ἐπισκιάζω ‘overshadowed’ the womb of Mary and become incarnate in the womb of the Virgin (Luke 1:35). This was understood as analogous to the enthronement of God on the ark of the covenant (Ex. 40:28 LXX). In Israel’s past, Yahweh had dwelt enthroned amidst the cherubim of the ark (Ps. 99:1; Isa. 37:16), in the incarnation, he dwells enthroned in the womb of a young woman from Nazareth. As St Hippolytus of Rome wrote:

…the things that took place of old in the wilderness, under Moses, in the case of the tabernacle, were constituted types and emblems of spiritual mysteries, in order that, when the truth came in Christ in these last days, you might be able to perceive that these things were fulfilled. At that time, then, the Saviour appeared and showed His own body to the world, born of the Virgin, who was the “ark overlaid with pure gold,” with the Word within and the Holy Spirit without; so that the truth is demonstrated, and the “true ark” made manifest.”

[St. Hippolytus, Commentary on Daniel 6.]

Mary is understood analogous to the ark, for in carrying Jesus in her womb, she becomes the vessel for:

The Word of God (Jn. 1:1, 14) – Tablets of the Covenant (Ex. 24:16; Deut. 31:24)

The True Bread of Life (Jn. 6:35) – The Manna (Ex. 16:33; Heb. 9:4)

The True High Priest (Heb. 4:14-16) – Aarons staff (Num. 17:10; Heb. 9:4)12

All of which St Paul mentions in his list in Hebrews 9. As Farley notes, “Just as God’s presence among men in the ark foreshadowed the Incarnation, so the ark containing God’s earthly presence also foreshadowed the Mother of God, whose womb would contain the Incarnate God… The [golden] jar [of manna] images Mary, who contained Christ and gave Him birth…[regarding the rod of Aaron] Christ… budded forth just as miraculously through the Virgin. Thus Mary is the rod, Christ the fruit, and His miraculous birth from her is a sign that saving and fruitful priesthood is only through Him.”13

The ark of the tabernacle was modelled on the heavenly ark (8:5). In St John’s vision, he sees the heavenly ark revealed before the throne in the heavenly temple, alongside the vision of the pregnant woman (Rev 11:19-12:2). Many Christian commentators see here a connection between the ark of heaven and the woman, drawing a connection with Mary, implying that “the woman, who is portrayed as the Mother of the Messiah (Rev 12:5) is in the same position as the heavenly ark, and is revealed in the same manner. For John then, the woman and the ark are dual symbols for the same reality.”14

As well as being imbedded within the Christological theology of the Church, the ark also came to be represented in the altar, itself situated in the sanctuary of the Church, typically behind a screen or curtain, as was the case in the tabernacle. The celebration of the Eucharist upon the altar recalls the contents of the ark. The reading of the words of institution (the tablets of the law), the offering of the eucharist (the manna) by the priest (the rod of Aaron) ties this symbology and typology together neatly. (cf. Ex 24:1-8) During the consecration of the eucharist, the priest performs or recites the ἐπίκλησις ‘epiklesis’, or the ‘calling down’ of the Holy Spirit upon the bread and wine – recalling the ἐπισκιάζω ‘overshadowing’ of the glory of God upon the ark and the Mother of God.

Conclusion

We can see then, that the ministry and liturgy of the Church of the New Covenant is the fulfilment of the priesthood and liturgy of the old. The Old Testament type is thus not irrelevant to the Church, but rather provides the essential framework and basis for its form and substance. For this reason, the understanding the tabernacle and its contents serve to illuminate the spiritual reality behind the worship of the new covenant in the Church.

These plans are also understood as being divinely inspired by the outpouring and inspiration of the Holy Spirit upon the craftsman who construct the tabernacle (Ex 31:1-11).

Lawrence R. Farley, High Priest in Heaven: The Epistle to the Hebrews (Indiana: Ancient Faith, 2013), 123.

Brant Pitre, Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper (New York: Doubleday, 2011), 129-130.

Pitre, Jewish Roots of the Eucharist, 131-132.

Pitre, Jewish Roots of the Eucharist, 133.

Farley, High Priest in Heaven, 123.

Harold W. Attridge, The Epistle to the Hebrews, Hermenia (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1989), 234.

Attridge, The Epistle to the Hebrews, 236-238.

Farley, High Priest in Heaven, 124.

Attridge, The Epistle to the Hebrews, 238.

Steven Bigham, Christians and Images: Early Christian Attitudes Toward Images (Rollinsford: Orthodox Research, 2004), 20-22.

Brant Pitre, Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary: Unveiling the Mother of the Messiah, (New York: Penguin, 2018), 52.

Farley, High Priest in Heaven, 124-125.

Pitre, The Jewish Roots of Mary, 50-51; Craig Koester, Revelation, 524.