The notion of an enchanted cosmos is one which is largely lost in today’s materialistic world. In the eyes of modernity, there is nothing else to the physical world around us other than… the physical world around us.

Nonetheless, when we turn to the pages of Scripture we find a very different world. In the biblical worldview, the cosmos is created for starters. And created by someone. What’s more, it is permeated, from the beginning, with the active Word of this creator, charged if you will, but the animated power of that divine utterance. This creative power drives the entire cosmos, in revolution around this creator, his design, his will, and his purpose, through all and in all.

Because of this, for the biblical author, there is much more to the created world than simply the observable reality. Indeed, the observable reality is intrinsically connected to the unobservable, and in many ways, the unobservable is more real than the observable. For it is in the realm of things that the reader cannot see that real power and purpose lie. Take for instance, the words of St. Paul;

“Set your mind on the things that are above, not on the things that are upon the earth…”

(Col. 3:2-4)

“For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of this world, against spiritual powers in the heavenly places.”

(Eph. 6:12)

In the Christian worldview, the realm of meaning is that of the heavenly, which fills all things here below with metaphysical purpose; and the real struggle, that which constitutes ‘reality’, is not the realm of ‘flesh and blood’, but rather that of the spiritual. In the Bible, the cosmos is a spiritual realm, as well as a physical realm, with spiritual entities as well as physical.

That is not to say that the physical realm, what we call ‘reality’ in our materialism, is not ‘true’ in any sense of the word, but rather that, to use the words of Plato, the physical realm draws it existence and meaning from a higher realm, from the eternal source of Being himself.[1] The physical world around us participates, reflects, and points us to the eternal realm of the spiritual, the realm which permeates all things. As the Psalmist states ‘creation declares the Glory of God” (Ps. 19:1). God, as scripture tells us, ‘is spirit’ (Jn. 4:24) ‘the invisible God’ (Col. 1:15) who dwells in ‘unapproachable light’ (1 Tim. 1:16). But in this, He is the ‘Father of lights’ through whom all good things come (Jas. 1:17), the very Light that permeates all things, (Ps. 72:19; 1 Cor. 15:28) and saturates the world around us with purpose and meaning, as his creation. Indeed, “in him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

Yet in this, we find, in truth, that our distinctions between ‘physical’ and ‘spiritual’ fall short in encapsulating the full sense of reality found in scripture. While our modern worldview drives a sharp wedge between the two, the authors of Scripture do not view the world this way. For them, the cosmos is both, together, intrinsically wrapped up in each other, inseparable.

Certainly, we do come across language of separation, for instance, in the words of Paul, who distinguishes the ‘fleshy’ from the ‘spiritual’ (Rom. 8:5-8; 1 Cor. 2:9-16) – but I would argue that, even there, Paul’s understanding of spiritual is not purely noetic, but rather is getting at the biblical notion of the fullness of reality permeated by the spirit. Having ‘new eyes’, transfigured to see the fullness of God in all things.

This is the Christian, indeed, the biblical worldview.

But when I reflect on whether we actually view the world in this way, I find that our modern Christian worldview is awfully flat. While it is certainly the case that some may view the world in this way, we find that most have little room for ‘spiritual things’. An intriguing reality, when we as Christians so faithfully confess our belief in

“One God,

the Father Almighty,

creator of heaven and earth,

of all things, seen and unseen”

(Nicene Creed).

The Scriptures portray a God of miracles, the Lord of the heavenly host, (themselves, tangible beings) and of course God made man, the ultimate affront to logical materialism. And yet we live our day to day lives in a world that has been largely stripped of any of this enchantment; a cosmos “stripped of the presence of the supernatural.”[2] What’s more, even our biblical reading and understanding is largely dis-enchanted, our bibles have “ceased to be a wonder-filled and sacred book.”[3] We no longer have eyes to see the framework, worldview, and the symbolism which so charged the scriptures with their ability to speak, reveal, and transfigure our hearts. Instead, the bible has largely, as has our worldview, become flat, dry and dusty. Both have ceased to be θεόπνευστος ‘God breathed’ (2 Tim. 3:16) As a result, the ‘living word of God’ (Heb. 4:12) has little to say to our modern world.

Re-enchantment

What is needed then is a breath of life to returned to the Scriptures, and in turn, our worldview. And the means by which to return this to the biblical worldview is through re-enchantment.

The word enchant comes from the Latin incantare which derives from the root cantare "to sing". This view of an ‘enchanted cosmos’ comes from the classical view of the world as held in balance by the celestial harmony, one charged with the divine word, and permeated with the song of creation.

The ancient Greeks viewed the sublime order and nature of the cosmos as expressed through music; the ‘musica universalis’. This is best expressed in Pythagoras’ ‘music of the spheres’, discussed in Aristotle’s On the Heavens. For later thinkers, this harmony was intrinsically linked with the terrestrial, in a sort of hierarchy. Boethius in his De Institutione Musica describes the three levels of the harmony, beginning with the musica universalis (the universe), then the musica humana, (the human body) and finally the music quae in quibusdam constituta est instrumentis (made with instruments).[4] Here, he references Plato’s notion of the harmony of the universal soul (Plato, Timaeus, 37) “united by a musical concord”.

These notions were also expressed by Christian theologians, who perceived in the Greek notion of the divine word or λόγος to the nature of the eternal Son (Jn. 1:1-4) and developed this idea extensively. Clement of Alexandria, in his Exhortation to the Greeks, directly relates the Platonic notion of the ‘music of the spheres’ to Christ:

“He who sprang from David, and yet was before him, the Word of God, scorned those lifeless instruments of lyre and harp. By the power of the Holy Spirit, He arranged in harmonious order this great world, yes, and the little world of man too, body soul together, and on this many-voiced instrument of the universe He makes music to God, and sings to the human instrument…”[5]

Clement notes that the Word permeates both the ‘great world’ ‘μακρός κόσμος’ and the ‘little world’, ‘μικρός κόσμος’ the two are interconnected, microcosm and macrocosm, the cosmos, and its inhabitant. Humanity then, serves a special role as the ‘image bearers’ of God – created as microcosm of the grand design of creation, made for relationship with God, and to share his presence and love with the created world, sharing in the great harmony of the cosmos.

Similarly, the 12th century nun and mystic, Hildegard of Bingen wrote concerning the creation:

[the elements of the world possess] a pristine sound that they had at the time of creation…fire has flames and sings in praise to God. Wind whistles a hymn to God as it fans and flames. And the human voice consists of words to sing paeans of praise.

All creation is a single hymn in praise to God…”

(Hildergard von Bingen, Analecta Sancta, 8.)

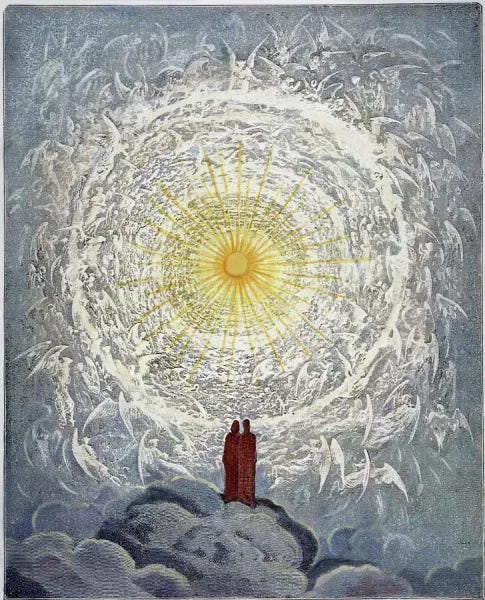

This, indeed, is a world incantare or ‘found in a song’. The meaning, purpose, and outworking of both is found through the harmony that weaves altogether, through the Spirit, via the Son, to the Father. Creation then is a participation of the triune nature of God, emanating from the love of God, driving the universe. As Dante writes in the final words of the Paradiso, that the world is being revolved,

“by the Love that moves everything…my desire and will were moved, like a wheel revolving in harmony, by the Love that moves the sun and other stars…”

(Dante Paradiso, 33:143-145)

Some Modern Portraits

While largely lost today, we still find hints of this worldview in the writings of perhaps the two last ‘medieval men’; Lewis and Tolkien.

Lewis, in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, speaks of the children’s encounter with a ‘retired star’:

“I am Ramandu. But I see that you stare at one another and have not heard this name. And no wonder, for the days when I was a star had ceased long before any of you knew this world, and all the constellations have changed.”

[But when I am once more young] I shall take my rising again and once more tread the great dance.”

“In our world,” said Eustace, “a star is a huge ball of flaming gas.”

“Even in your world, my son, that is not what a star is but only what it is made of.”

(C.S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 117.)

Indeed, the stars ‘are not just stars’, but sentient creatures who partake of ‘the great dance, and are renewed from their rest to join once more in the great song of the heavens. Later, in his Space Trilogy, Lewis would speak of the stars as animated by the angels, who he describes as

“those high creatures whose activity builds what we call Nature’.

(C.S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength, 199.)

Similarly, in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion, the creation of the universe takes place through the Ainulindalë or ‘song of the Ainur’, Tolkien’s ‘angels’:

“There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought, and they were with him before aught all else was made. And he spoke to them, propounding to them themes of music; and they sang before him, and he was glad…the voices of the Ainur, like unto harps and lutes and pipes and trumpets, and viols and organs, and like unto countless choirs singing with words, began to fashion the theme of Ilúvatar to a great music; and a sound rose of endless interchanging melodies woven in harmony that passed beyond into the depths and into the heights, and the places of the dwelling of Ilúvatar were filled to overflowing, and the music and the echo of the music went out into the Void, and it was not void.”

(J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, 3.)

In all of these creative visions, the cosmos it not simply a material reality, but one that is deeply entrenched in spiritual enchantment, permeated through and through with divine presence. Indeed, in this God is not the only spiritual being – this is a world wherein stars are sentient and dance before God (Job. 38:7), where spiritual and material both partake in the created order, and where humanity, in their lives and activities, participate in the great celestial song that hymns and praises the Father of Lights.

The thing is…this is our world too. We have just forgotten it.

Lewis, in his The Discarded Image, in reference to the more enchanted aspects of creation, notes that these aspects are not gone, but that we as moderners have largely lost the ability to see them:

“One might have expected the High Fairies to have been expelled by science; I think they were actually expelled by a darkening of superstition.”

(Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature, 72).

A ‘darkening of superstition’ indeed... a poignant phrase. Perhaps, another way of putting it would be, ‘lack of an ability to believe’? A loss of the ability to see the world, indeed, ourselves, as thoroughly enchanted, and permeated by the creative presence of God.

***

[1] Plato, Republic, VII:514-517, (London: Penguin Books, 1987), 256-260. See also: Plato, Phaedrus, 270b-279c.

[2] Cheryl Bridges-Johns, Ren-enchanting the Text: Discovering the Bible as Scared, Dangerous, and Mysterious, (Grand Rapides: Baker, 2023), 3.

[3] Bridges-Johns, Ren-enchanting the Text, 25.

[4] Boethius, De Institutione Musica, I:2

[5] Hans Boersma, Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early Church, (Grand-Rapids: Baker Academic, 2017), 140.